Indirect Communication and Conversational Worlds

It may seem curious to the reader that we admit machines to the field of language and yet almost totally deny language to the ants.

– Norbert Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings, 1950

In the summer of 2020, I remember spending hours in a warm haze half-watching my friend Dan play Death Stranding. Often somewhat unkindly referred to as a “walking simulator,” Death Stranding is a game where the player navigates the world as a delivery worker, tasked both with supplying and gradually reconnecting a network of cities in a post-apocalyptic North America. Navigating the game, Dan would increasingly encounter items and signs left by other players – traces left in the fabric of the game, a rudimentary messaging system between ghosts, a one-sided conversation. There was an intimacy and generosity to this anonymous messaging – completing a delivery felt like picking up a sentence where someone left off, while signs and warnings became gifts passed through space-time.

Stigmergy describes a form of communication where the environment becomes part of the messaging medium, through fragments of memory that are spatially distributed. The classic stigmergic system is the ant colony: equipped with a small repertoire of pheromones and rudimentary sensory perception, ants communicate by leaving chemical traces for one another, a messaging system that both shapes, and is shaped by, the surrounding environment. In contrast to other forms of social organization, activity is highly decentralized – interagent communication is enough to maintain a functioning and resilient system without the need for top-down orders. Within the world of Death Stranding, the comparison is quite clear: “messages” left for other players are almost entirely material, one-bit information that nonetheless develops an emergent complexity that proves indispensable for gameplay. However, all conversational environments, to some extent, construct and are constructed by the world in which they take place.

Games provide a rich territory for the discussion of environmental conversation systems. In Dwarf Fortress, for example, machine conversations are woven into the narrative of the game, with each character generating a long account of interactions (with other characters, plants, walls, etc.) that builds up their personality over time. As the player, however, you don't get to speak or even structure these conversations: simply setting the world in motion generates the dialogue. In many MMOs, the game exists in parallel to ongoing and obliquely related conversation – in-jokes and memes among players weave the fabric of an otherwise loosely constructed world, almost like a chatroom with legs.

What does a world look like that is explicitly rather than implicitly structured by conversation? I often come back to a scene in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, where the protagonist Arthur Dent boards a spaceship, the interior of which resembles an Italian restaurant. To his bemusement, his companion informs him that the ship is powered by Bistromathics, a field of maths that uses the complexity of interactions between patrons and staff to power a kind of random number generator, steering the ship. Would a game like this be fun to play? Perhaps not – the “real” dynamics of the conversation, while powerful, are almost entirely hidden from the participants.

Of course, in all conversations, more is always there than is actually being said – considered in their totality, all but the most simple messaging systems contain layers of hidden meaning. The cyberneticist Gordon Pask – who coined the term “conversation theory” – differentiates between the two dimensions of a conversation as an object-language and meta-language, the latter of which might be wholly or partially concealed from the participants.1 The object-language is what the conversation is stated to be about; the meta-language constitutes a discussion of the conversation itself, which might be more or less easy for the participants to access and consciously address. I find the idea of hidden conversation dynamics within the context of feedback systems very compelling – thinking about the loops between what a particular conversation seems to be from the outside, versus what it actually does to the world and the people in it. In every conversation, there is the literal exchange of information between agents, and there is the latent transformation of and feedback from their shared environment, a form of what we might term “stigmergic dialogue.”

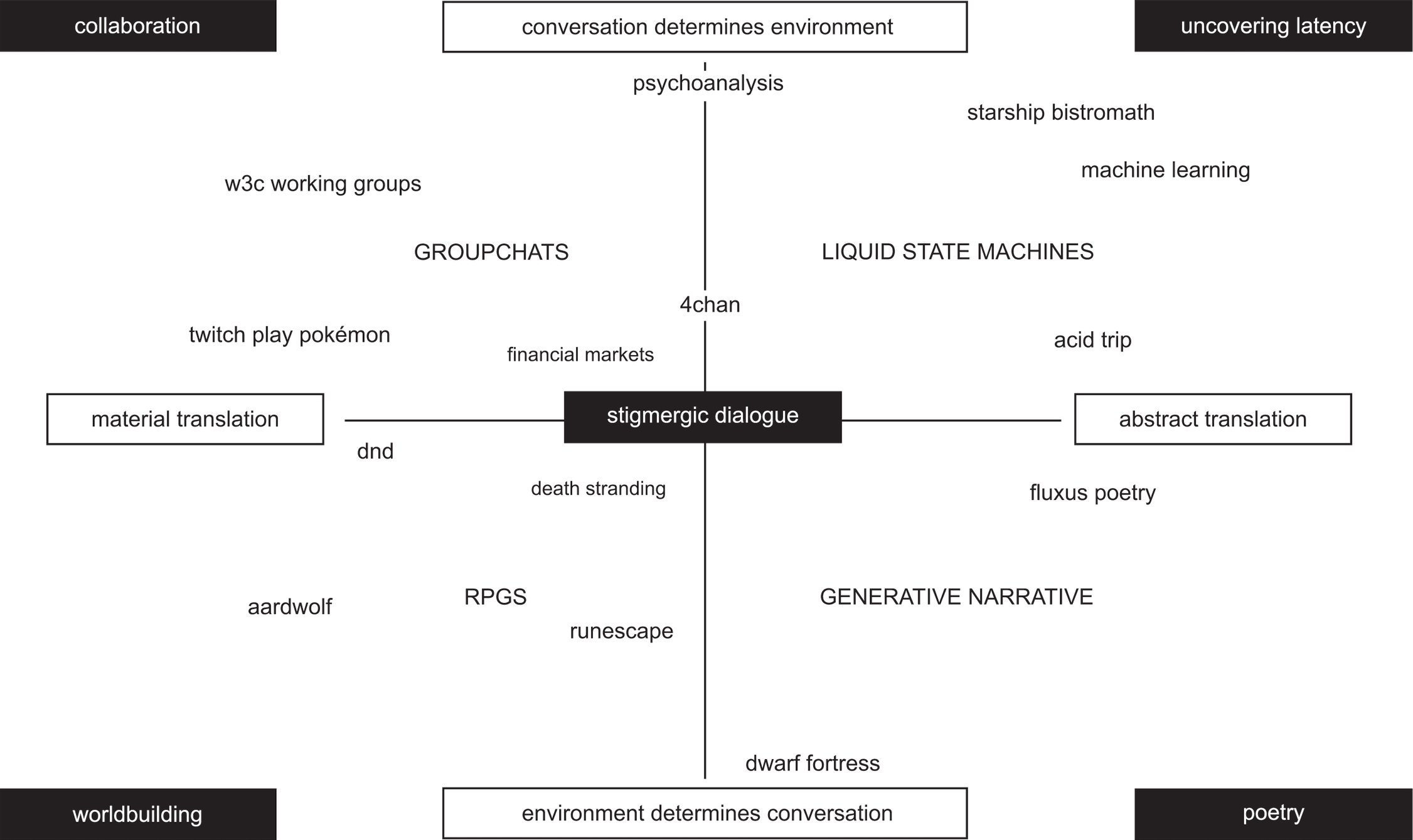

While this tension is present, to some extent, in all conversation systems, I am interested here in worlds that strike a balance between these forces of environmental and latent feedback. To me, this balancing act is akin to Fabian Fischer’s “Criteria for Strategy Game Design,”2 in which he posits that an “interesting” decision in a game sits somewhere between a solution and a guess. Of course, a conversation can be “interesting” in terms of its subject matter – but what makes for an interesting conversation system? To think about this, I laid out a chart that relates what I would consider the core dynamics of stigmergic dialogue:

One is the materiality of the translation: “what you say is what you get” versus systems that operate based on latent aspects of the conversation. This is similar to Pask's object-language/meta-language dichotomy, though both the object- and meta-language are present in every conversation system to some degree. Particular to systems near the center of this axis are structures where the point of the conversation is meta-conversation – psychoanalysis is an obvious example, where unconscious dynamics are constantly addressed, but 4chan’s chaotic self-referentiality also follows this structure.

The other axis varies the extent to which the “important” factors in an environment (note that which factors are considered important will always be subjective) are controlled by conversation versus the extent to which the environment dictates the conversation. Systems toward the center of this axis tend to have quite a rich environmental feedback system, ranging from the collaborative (DnD) to the chaotic (acid trip).

I’ve tried to characterize the “vibe” of each quadrant – collaboration, worldbuilding, poetry, uncovering latency – and would argue that an interesting Autonomous World contains elements of each. What I would call “stigmergic dialogue” sits at the center of these relationships: the idea of feedback between an environmental system and a conversational one, and the presence of a latent control language that participants can nonetheless participate in and perturb.

What this might mean for the design of conversation systems is an interesting question. It’s remarkable how few multiplayer games structure conversation more intentionally than a formless spatial “chatroom” between players, making those that do feel quite remarkable. In Death Stranding, for example, a strongly stigmergic effect was achieved by heavily limiting what players could “say” to one another, making the conversation entirely unidirectional and environmentally mediated. Collaborative systems like Twitch Plays Pokémon3 and financial markets also have strictly defined rules about how communication happens. 4chan, while ostensibly totally unconstrained because of its anonymity and speed, actually experiences constraint for the same reasons – memes ride on waves of circular memory amongst participants; a critical mass of people “in the know” is required to maintain collective energy.

In part, one could put the vibrancy of these systems down simply to “emergence” (where participants in a system self-organize into a more complex structure), but a key characteristic of emergent systems is the existence of strong constraints that permit a decentralized communication system to form. Perhaps it’s more interesting to argue that, by structuring a dialogue system that’s necessarily embedded within and constrained by its environment, worlds themselves become an emergent phenomenon of communication.

Acknowledgements

This text was originally published in Autonomous Worlds N1, 2023.

Footnotes

-

Gordon Pask, An Approach to Cybernetics, Hutchinson, 1961. ↩

-

Fabian Fischer, “Criteria for Strategy Game Design,” Game Developer, 2014. ↩

-

Created by an anonymous Australian programmer in 2014, Twitch Plays Pokémon is a social experiment in which Twitch-users control a character by writing game-inputs directly into the chat. ↩